Parašė www.lithuaniatribune.com

Daumantas Levas Todesas, the organizer of the photography exhibition “A Kaddish for the Wooden Synagogues of Lithuania” at Vilnius Town Hall has many plans for the time ahead. Having acquainted Vilnius residents with the Lithuanian Jewish heritage that has fallen into decay, the head of the Jakovas Bunka Charity and Sponsorship Fund is now planning to take the exhibition to European countries.

Daumantas Levas Todesas, the organizer of the photography exhibition “A Kaddish for the Wooden Synagogues of Lithuania” at Vilnius Town Hall has many plans for the time ahead. Having acquainted Vilnius residents with the Lithuanian Jewish heritage that has fallen into decay, the head of the Jakovas Bunka Charity and Sponsorship Fund is now planning to take the exhibition to European countries.

We asked Mr. Todesas: How did you come up with the idea to organize a photography exhibition of abandoned wooden synagogues?

– Firstly, photographs of five wooden synagogues in the archives of the Department of Cultural Heritage caught my eye. I wondered how many such synagogues were left in Lithuania. Therefore, last May I started travelling around Lithuania in an attempt to record them.

Another thing that aroused my passion for collecting photographs was words by Paulius Galaunė, a famous interwar Lithuanian art critic and cultural heritage protector, that synagogues were not only Jewish, but also part of the Lithuanian heritage. Indeed, I think that the notion “Lithuanian folk art” is misleading. We should talk about Lithuanian folk art. We, the Jews, have lived here for 700 years and we are the creators of Lithuanian culture just as Lithuanians and other local ethnic groups who have lived here for centuries.

This exhibition aims to engage with ethnic diversity and show that this heritage is not only Jewish, but also Lithuanian.

– What is the purpose of recording the condition of these buildings? Are you going to restore these heritage buildings and turn them into houses of prayer again?

– These synagogues are a lost world. No one will ever light candles or unroll a Torah scroll here.

These synagogues will never perform their former role, because the communities were exterminated during the World War II. There are no people left and we need a minyan (a quorum of ten or more adult male Jews) for communal prayer.

There are no more Jews. Therefore, our job now is to save the buildings and, at least, help people gain the understanding that they are not just ordinary houses.

– Perhaps the buildings will be made into museums?

– Museums? I do not think so. If we manage to raise the necessary amount of money, we shall restore the buildings, but they will never be used again. They are dying despite their outer shell.

How could these buildings be used? There are three essential ways of using them. Firstly, the buildings can have an educational function. Lessons can take place there to help answer the questions: Who is a Jew? Where do they come from? What about their life here for so many centuries?

Secondly, the buildings are a means to teach about the Holocaust and, finally, they can be used for religion. Young people nowadays do not know that there is only one God and that Christianity has Jewish roots.

– You’re not the first ones to take pictures of abandoned synagogues…

– No, but people before us did this only for documentation. They only aimed to prove the fact that these buildings exist, to measure and describe them. And that was it. There was no money. Perhaps the main problem was not the money, but the lack of will or determination to do something to save them.

– The exhibition captures a glimpse of nine synagogues. How many remaining wooden synagogues now standing in Lithuania do you know?

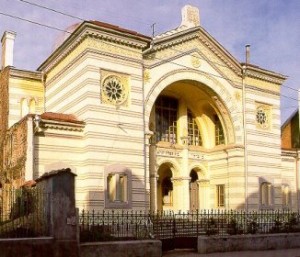

– Before the war, there were over 500 brick synagogues in Lithuania. The number of wooden synagogues is considerably lower. Today there are 17 or 18 surviving buildings; four of them are houses of prayer. Actually, that’s a lot because there are about thirty wooden synagogues in Europe. It means that more than half of all European wooden synagogues are in Lithuania.

– What about their condition today? Are they all equally abandoned?

– Unfortunately, synagogues in Lithuania have not been used for their purpose for more than 60 years and as a result hey are disappearing in a puff of smoke. The best example is the synagogue in Seda. The photograph taken in May 2011 reflects the building in quite a satisfactory condition and just before the New Year it is collapsed. So we actually see with our own eyes that our heritage is disappearing, because no one took care to preserve it.

The worst of it is that these buildings do not have an exclusive exterior, so people do not recognize them as houses of prayer. Some of them have been turned into warehouses, but it certainly is not the worst example. There are worse cases, when unfitted wooden synagogues were turned into bath houses or pigsties.

However, there are also some good examples of local communities and authorities taking joint action to preserve these historic buildings. Likewise happened in Pakruojis. Some activists and the municipality joined forces and took steps to preserve the building. Support was allocated from Norwegian funds to protect the building from further decay. The synagogue was provided with a new roof. Of course, a lot of time and money is required to renovate the building, but a good beginning makes for a good ending.

Hustle and bustle is also felt in Alanta. Danielius Drazdauskas, the chairman of the community of this small town, is a very active man. He found me and asked me what to do. So I said: “There are no Jews. We must ourselves do something about it. If the community wants it, then it will be.” When the winter cold recedes, I plan to go there and measure everything, make an estimate and then raise the money.

What else? The house of prayer in Alsėdžiai received major renovation. It has a very well-equipped garage.

– Do you plan to travel around Europe with the photography exhibition?

– Yes. I cannot confirm it yet, but we are negotiating with the Poles and the Dutch. So we shall go to Poland or to the Netherlands.

– One of the fund’s plans is to set up an ethnographical Litvak village in Žemaitija (Samogitia). Is this going to be a Jewish equivalent of Rumšiškės?

– We have paid tribute to the dead already. And we all know how we have died. Now it is time for people to find out how we used to live. We have counted over 290 locations where Jews lived in Lithuania, and we plan to create such a map in the territory of 6 ha, near the Žemaitija National Park.

The museum in Rumšiškės opened at the time when Lithuanians needed to emphasize their own national identity, ethnicity, so there was no place left for the Jews in their ethnographical village. Although this is historically wrong. There were at least three Jewish buildings in every Lithuanian village: the mill, tavern and smithy. There were even more such buildings in small towns. Moreover, Jews tried to build at least one building with a high-rising roof for the meetings in every village.

Published by Vilniaus Diena on 8 February

Translated by Ministry of Foreign Affairs